[TIPS] The Toxic State of Public Discourse and How to Clean It Up

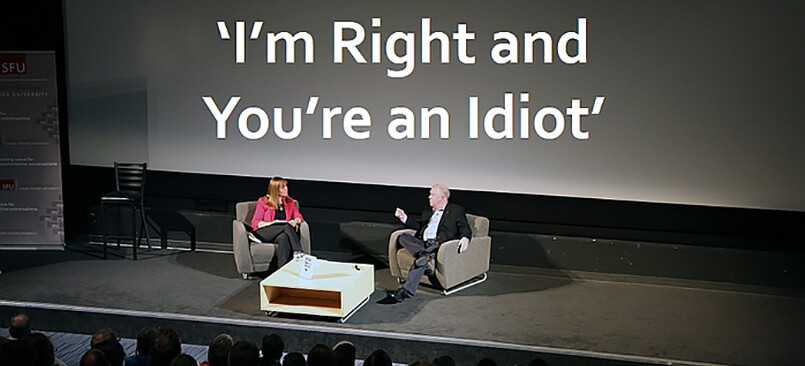

Image from book launch event courtesy Hoggan & Associates

My interview with Author James Hoggan: ‘I’m Right and You’re an Idiot: The Toxic State of Public Discourse and How to Clean It Up’

Published by New Society, May 2016

James Hoggan has influenced my work for two decades. I find myself quoting his work in many of my public speaking engagements and the lessons he has articulated have shaped MetroQuest and the best practices listed in our guidebook in numerous ways. Naturally, I jumped at the opportunity to sit down with Hoggan to discuss his new book, “I’m Right and You’re an Idiot: The Toxic State of Public Discourse and How to Clean It Up.” After years of research that included interviewing some of the world’s most profound thinkers on democracy, conflict and consensus-building, Hoggan has cleverly articulated not only what’s wrong with public discourse but also what must be done to fix it. Here’s our conversation.

Dave Biggs: You named your book ‘I’m Right and You’re an Idiot.’ What does that title mean to you?

James Hoggan: The title I’m Right and You’re an Idiot describes today’s warlike approach to public debate. It’s a style of communication that polarizes public conversations and prevents us from dealing with the serious problems stalking everyone on earth.

It is an ironic title, chosen because it epitomizes the kind of attack rhetoric we hear so often today. It reflects the opposite of the real message of the book, which was best said by peace activist and Zen Buddhist monk Thich Nhat Hanh who told me to: “Speak the truth not to punish.”

Dave Biggs: It’s clear that you covered a great deal of ground in researching this book. Tell me about that journey? What motivated you to go to such lengths?

James Hoggan: I was driven by curiosity about how we might create the space for higher-quality public conversations. What passes for public discourse these days is little more than antagonistic name-calling, where each side accuses the other of bad faith.

This bitter combativeness has replaced healthy debate, during which passionate opposition and science can shape constructive mind-changing conversations without creating polarized gridlock or deep animosity.

I am interested in why are we listening to each other shout rather than hearing what the evidence is trying to tell us about problems such as climate change.

How have we come to a time when facts don’t matter and how can we begin the journey back to where they do?

No single person has the answers to these complex questions but collectively the experts I interviewed offer incredible wisdom. Many of the thought leaders I spoke to have spent their entire professional lives working to find answers to these tough change resistance questions.

Dave Biggs: Many of our readers are involved in community engagement for planning projects and, as they can attest, it can get quite heated. You describe public discourse as increasingly “toxic” and “polarized.” What do those terms mean to you? Is the situation getting worse? What’s driving it?

James Hoggan: Today’s public square is a toxic mix of ad hominem attacks, tribalism and unyielding advocacy. It’s a kind of pollution that sabotages public discourse and discredits the passion and outrage at the heart of healthy public debate, because it polarizes people and stops them thinking clearly.

Fear is what propels toxic discourse and it is happening on both sides of the Atlantic, in North America and Europe. Sadly, facts do not compete well when leaders whip up primal feelings around fear, whether it’s about immigration, jobs or economic woes.

Rather than confronting the substance of an argument itself, people tend to attack the motives of opponents and stir up hostility towards groups that hold differing opinions.

This dangerous habit of attacking the character of those who disagree with us, rather than focusing on specific issues, distracts the public from what’s really going on.

Accusing opponents of corrupt motives is a highly confrontational technique that deflects attention and makes it easy to dismiss well-founded criticism. This aggressive approach to public debate leaves little room for the middle ground and as Debra Tannen wrote, “When extremes define the issues, problems seem insoluble and citizens become alienated from the political process.”

Dave Biggs: I’ve started a series called “Fiasco Files” to see what can be learned from the wreckage of public engagement disasters. Have you looked at specific case studies where things went off the rails? Does your book point to common mistakes and how to avoid them?

James Hoggan: One of the best example of a fiasco in Canada was in 2012 when the oil & gas industry and Conservative government campaigned to convince Canadians that British Columbians who opposed pipelines and tankers on the west coast were extremists working for American business interests.

A tremendous amount of information was provided, by both government and industry, regarding Kinder Morgan’s Trans Mountain Pipeline expansion, Enbridge’s Northern Gateway Pipeline project and TransCanada’s Keystone XL and Energy East.

Despite armies of PR people and volumes of communication materials, the mismanagement of communication around these proposed oil sands developments became textbook examples of how not to achieve social license.

When it comes to public opinion, there’s a common belief among proponents that providing facts is the best way to sell a story. But in the oil sands case, when the companies and government failed to achieve their goals, they resorted to a combative, underhanded style of advocacy.

The Prime Minister’s Office called opponents “foreign funded radicals.” The Minister of the Environment and the Minister of Natural Resources accused environmental charities of criminal activity.

Senator Don Platt said ‘where would …environmentalists draw the line on who they receive money from. Would they take money from the Al-Qaeda, the Hamas or the Taliban…’

This highly polarizing strategy backfired badly as opposition to pipelines grew and community groups and First Nations became better organized. It failed because the government and industry started with a mistaken assumption that anyone who disagreed with them was either misinformed, unreasonable or even a wrongdoer.

Despite assurances from oil and pipeline companies that these projects will create jobs, are safe and will respect the environment, the public continues to see the benefits as small and the risks as unacceptably high.

It’s not that information doesn’t matter, but a growing body of research on how people develop perceptions of risk shows that facts and statistics alone do not change people’s concerns about what is risky. Emotions play a huge part.

University of Oregon psychologist Paul Slovic has studied the various social and cultural factors that lead to disputes and disagreements about risk, and says the problem lies in the diverse ways in which “experts” and the public view risk.

Experts look at risk as a calculation of probability and consequence. The public takes a more personal approach; their perceptions are around personal control, voluntariness, children and future generations, trust, equity, benefits and consequences.

Slovic says the mistake experts (and the companies and governments they represent) make is viewing themselves as objective and the public as subjective.

They perceive the public as being too emotional and having irrational fear. The public’s attitude is then dismissed as laypeople getting the facts wrong and not understanding the evidence.

“Laypeople sometimes lack certain information about hazards,” Slovic says. “However their basic conceptualization of risk is much richer than that of experts and reflects legitimate concerns that are typically omitted from expert risk assessments.”

This is where a company’s decision to “educate” the public to adopt its point of view can really backfire. People aren’t sitting around waiting to be told what to think. In fact, few of us like being told what to think.

Communicators need to be sensitive to this broader concept of risk. Facts aren’t just facts. They aren’t as objective as we assume they are. Facts and risk are subjective for both experts and the public. They are a blend of values, biases and ideology.

The hypodermic needle theory of communication, where we believe we can simply inject information to cure people of their misunderstandings, doesn’t work. Neither does demonizing opponents or polarizing people.

Dave Biggs: I’m always on the lookout for emerging best practices in community engagement. Government agencies are hungry for strategies to improve the dialogue in face to face events as well as online. What lessons can you share to help them broaden the dialogue to a wider demographic and collect meaningful and constructive public input to inform their decision making?

James Hoggan: We often don’t even get the basics right. Learning to engage in emotional dialogue is a good place to start.

Curtailing the growth of unyielding one-sidedness begins with the assumption that people who disagree with us have good intentions. They aren’t idiots or evil.

It is important to recognize that in a time when mistrust and polarization have soared to all-time highs, conversations aimed at injecting information into people in order to cure them of their misunderstanding will fail.

The power of emotion is a critical consideration. No matter how good you think your argument is, regardless of how provable your facts, if the public feels its liberty, right to fair treatment or livelihood is threatened, you’re losing the battle to dread.

Opposition is often based on feelings of dread that citizens have about the impact a project could have on their way of life, a mistrust of the companies behind it and skepticism around government regulators charged with oversight.

Fear can grow despite a steady stream of facts and expensive PR campaigns from proponents claiming their projects are built to minimize risk.

Opponents often don’t accept the proponents’ facts, but are instead driven by what Paul Slovic calls the “dread factor” — the prime predictor of a strong reaction to risk.

According to Slovic, risk resides in us mostly as a “gut feeling” rather than the outcome of analytical calculations. The most powerful of these feelings is dread and it is linked with a sense of having no control in a situation, inequality (where others get the benefit, while they get saddled with the risk) and how catastrophic a risk is seen to be.

His research shows that reliance on feelings as our guide to risk causes us, when we see risk as high, to also believe the benefit is low. The opposite is true if we come to believe the benefit is high, we tend to see risk as low.

Misunderstanding the “dread factor” and the possibly legitimate concerns that fuel it, intensifies the problem of unyielding one-sidedness that we see in so many public disputes.

It is also difficult to be seen as authentic in an argument if you don’t understand what Slovic calls the “whisper of emotion.” This is the emotional meaning; the good or bad feelings and gut instinct that can help people make decisions. Sometimes these feelings are misguided, but they are usually a sophisticated compass that directs us through life efficiently and accurately.

We need to be more conscious of emotional dialogue because this is where most risk communication fails. And we need to recognize it needs to be a two-way process where both sides have something worthwhile to contribute.

If you hold your views lightly and remember you could be wrong, people are more likely to trust you and be more receptive. It’s about communicating trust, by having an open mind, open heart and an open will.

This post was published in Planetizen here.

Wow, thanks for the substantive and nuanced discussion of a crazymaking, challenging dynamic. Concepts I’ll be re-reading, sharing and hopefully integrating.

Timely, insightful and accurate – thanks Dave a really excellent exposition of why so many of our projects fall on deaf ears and the attempts of communication departments to redress this only serve to stuff it up more! Will be distributing to a number of my key clients and, of course, buying the book!

Excellent dialogue. Here’s my take: Before trust, we must have respect. Often there is no respect in the first place. A tone must be set to infuse respect into the dialogue. No respect. No trust. No honest dialogue.

[…] NCDD member Dave Biggs recently published the insightful interview below via MetroQuest – an NCDD member organization – and we wanted to share it here. Dave interviews the author of a new book, I’m Right and You’re an Idiot, on the way emotion and perceived risk contribute to polarization and toxic public discourse, and how understanding the psychology of our “emotional dialogue” can help us build bridges to understanding. We encourage you to read the piece below or find the original version here. […]

I hope the book addresses the important factor of asymmetric power, i.e., that ordinary folks who may be “at risk” generally have much less power than proponents or government employees in the critical decisions.

From this starting point, when the more vulnerable see one-sided advocacy, no matter how “cloaked” the message is, coming from government organizations that should be “neutral,” the level of mistrust goes up, which increases the perceived likelihood that bad things are going to happen no matter what, which feeds dread.

The comment that “before trust we must have respect” is exactly backwards! Respect is earned, not given. You want respect? Then be trustworthy above all else. You can directly control how trustworthy you are. You cannot control how much others respect you, except through your actions, past and present.

Thus, this is not a “which came first, the chicken or the egg?” situation. The starting point is not “respect” from ordinary folks. The starting point is trustworthiness by the proponents of some course of action and the public employees who are supposed to be serving the interests of community members.

— Paul

Thanks for finally writing about >The Toxic

State of Public Discourse and How to Clean It Up

– MetroQuest <Loved it!